Rhyolite Ghost Town

If there’s one place where Nevada excels, it’s our amazing and accessible ghost towns—with plenty ripe for on-foot exploration. One of the best examples is Rhyolite ghost town, which sits just off the highway to Death Valley National Park. Not only is Rhyolite packed with plenty to do, it also boasts some of the West’s most iconic ruins.

Rhyolite is one of the most photographed ghost towns in the West. Stop in during your Free-Range Art Highway adventure to find out why.

History of Rhyolite, Nevada

In 1904, prospectors Frank “Shorty” Harris and Ernest “Ed” Cross were exploring the desert hills on Nevada’s western border when they discovered high-grade gold ore. They named their claim Bullfrog—after the area’s green-hued rocks—and within a year, several mining camps were set up nearby, adding to what became known as the Bullfrog Mining District.

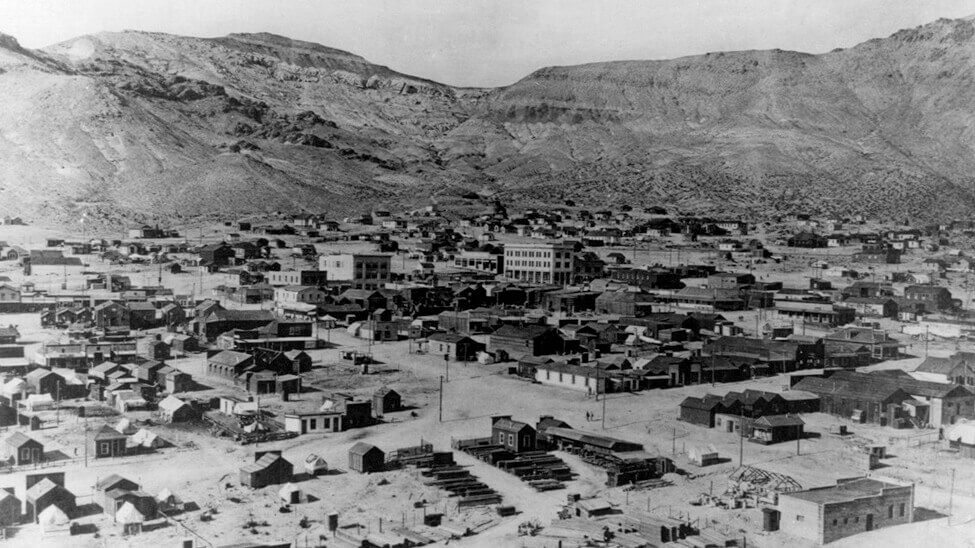

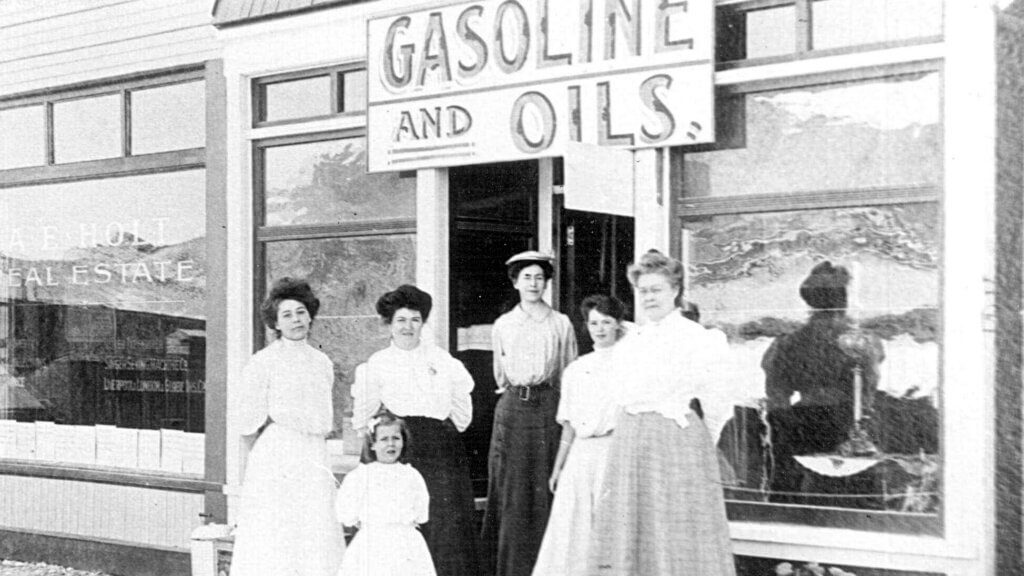

Word of this wildly lucrative operation spread all the way north to Goldfield and Tonopah, and people began arriving by the thousands. During this rush, four daily stagecoaches connected “The World’s Greatest Gold Camp” to the Bullfrog Mining District, ushering in a steady flow of people to Nevada’s newest gold discovery. In 1905, the town of Rhyolite was founded in the heart of the Bullfrog Mining District. What started as a two-tent mining camp boomed into a bustling town of around 5,000 people within six months. While mining camps were very common in Nevada during the late 1800s and early 1900s, Rhyolite stood out for its valuable ore samples.

As if Rhyolite sprung to life overnight, this community quickly became the epicenter of the Bullfrog Mining District. Aside from a swelling population, Rhyolite boasted:

- 50 saloons

- 35 gambling tables

- 19 lodging houses

- 16 restaurants

- Several barbers

- A public bath house

- A red light district

- And a weekly newspaper publication called the Rhyolite Herald

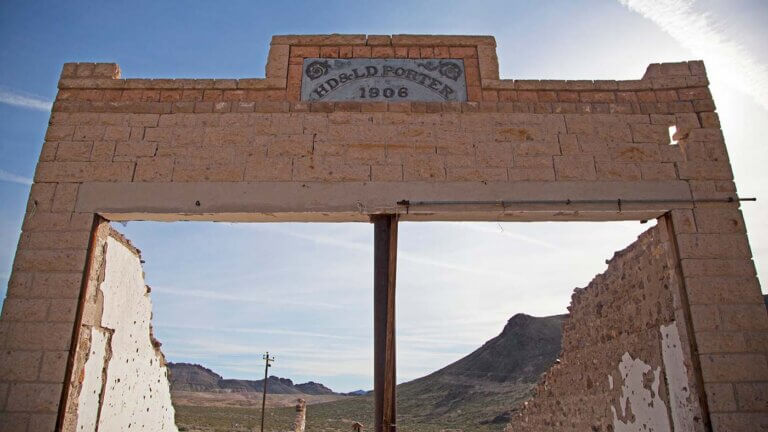

Rhyolite was so successful that it soon caught the attention of steel magnate and savvy businessman Charles M. Schwab. In 1906, Schwab purchased the Bullfrog Mining District, which elevated the operation from good to grand. With Schwab’s leadership, Rhyolite secured a contract with the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad, and within a year, three railroads were connected to Rhyolite’s brand-new—and still perfectly preserved—train station.

Also thanks to Schwab, Rhyolite residents enjoyed luxuries not usually associated with mining boomtowns like concrete sidewalks, telephone lines, electric street lamps, and plumbing. Downtown’s commercial buildings—many built from stone—included a hospital, three banks, a stock exchange, an opera house, a public swimming pool, and two churches.

Rhyolite, Nevada’s Bust

While Rhyolite and the Bullfrog Mining District produced more than $1 million within three short years—about $27 million by today’s standards—this boomtown declined almost as rapidly as it came to life. Like most other has-been mining communities, the high-grade ore began to diminish, and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake proved to be the kiss of death as the rail service was seriously disrupted.

By 1910, mines began to close, businesses failed, and workers sought employment elsewhere. By 1914, the city lost electricity, and the banks, newspapers, post office, and train depot all closed. In 1920, only 14 people called Rhyolite home.

Because timber and stone were rare resources in the desert, most of Rhyolite’s infrastructure and buildings were taken apart to be used elsewhere. In nearby Beatty, material was recycled to make new buildings, including the schoolhouse. Sometimes entire buildings were moved, like The Miners Union Hall, which is now the Old Town Hall in Beatty. In 1913, one of Rhyolite’s original saloon bar tops was relocated to Goodsprings, where it is still a fixture in the Pioneer Saloon.

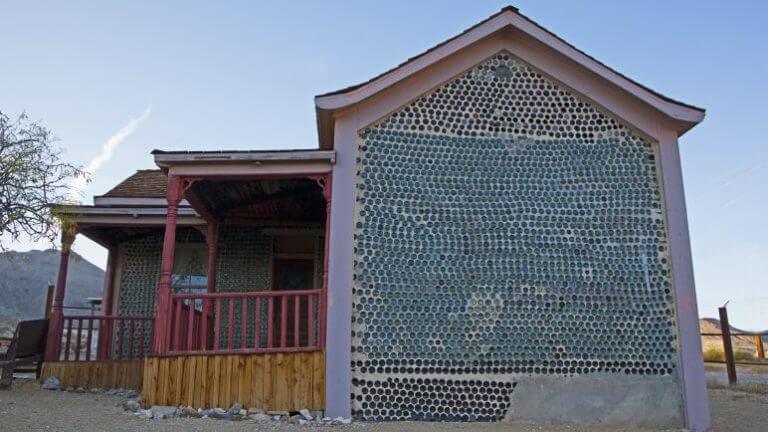

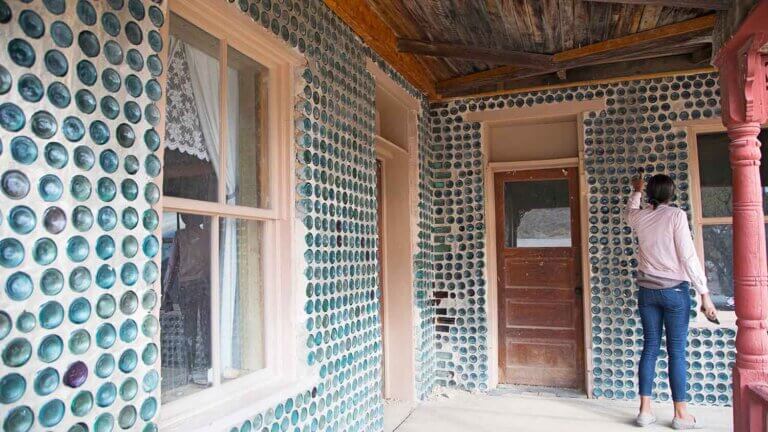

Tom Kelly’s Bottle House

Though the lights went out in 1914, they turned back on a decade later when Paramount Pictures used Rhyolite as a setting for the 1926 film The Air Mail. Some of Rhyolite’s remaining structures were restored for their film debut, including the Tom Kelly bottle house. This residence—built completely out of 50,000 medicine, whiskey, and beer bottles—demonstrates that glass in the American West was sometimes a cheaper construction material than wood or stone. The house still stands today and is the oldest and largest known bottle house in the United States.

Goldwell Open Air Museum

Aside from being featured on the silver screen, area tourism soon began to flourish after the opening of Death Valley National Monument—now Death Valley National Park. Rhyolite saw a wave of visitors beginning in the 1930s, and the remains of the ghost town became a protected site. In 1984, Belgian artist Albert Szukalski created his sculpture rendition of “The Last Supper” nearby, and today, around a dozen art installations live in what is now called the Goldwell Open Air Museum. This open air art gallery is located just below the remains of Rhyolite.

Travel Nevada Pro Tip

Hours:

Rhyolite ghost town is open and welcomes visitors every day of the year from sunrise to sunset.

Admission:

Rhyolite ghost town and the Tom Kelly Bottle House are managed by the Nevada Bureau of Land Management, making free public access available to all.

This Location:

City

BeattyRegion

Central